I have long been a fan of Classics and classical history, and though I ply my trade as a Homerist, I have been fascinated with ancient battles and military tactics. In teaching courses on Ancient Greek history, however, I have found many students confused by the issues that attend evaluating narrative descriptions of battles and even less prepared to critique either the presentation of the battles or the tactics themselves.

Part of this reluctance, I believe, comes from the fact that we don’t teach military history as much as we once did and, perhaps more importantly, from the distance between the lives of our students, the military realities of the ancient world, and the mechanized, specialized actions of the modern-day. I have long suspected that getting students to model battles either with their own bodies or with some type of game pieces would improve the way that they understood ancient warfare. I was surprised when I actually tried it out to discover just how effective it was.

Modern studies in pedagogy have noted the effectiveness of using role-playing in the classroom from fake trials and writing in others’ voices, to large-scale gaming (see, for example, Mark C. Carnes’ Minds on Fire: How Role-Immersion Games Transform College>). Research in this area, I must confess, conformed to my own personal biases: I always suspected that my hours of Dungeons & Dragons (ok, years—I played a bard to the 22nd level in Advanced D&D) and endless games of Risk and similar strategy games (Battlelore among others) had shaped the way I read about ancient battles. But it was only when I started working on modeling battles with students that I realized how important the hands-on approach could be.

The Idea

Although there is a healthy and impressive culture of online and board-based war-gaming and re-enactments, I wanted to create an interface that was fast, easy-to-learn and easy to assemble, i.e. something I could execute in one or two classes with students who had next to no experience with gaming. In addition, I wanted the interface to be easily adaptable to different battles, cultures and contexts. Finally, I wanted game-play that could be updated on the fly and pieces that were cheap, re-usable and easy to get.

I first experimented with Roman Empire Maps using Risk pieces and basic risk rules (inspired by the Android Game LandRule. The province-based game, while fun with students, doesn’t actually teach much about military tactics and different units or allow for the re-enactment of simple battles.

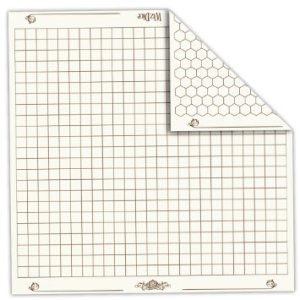

So, my next plan was to use the pieces from a Risk set (and I own 6 sets) on a simple hexagonal gaming board (available in re-usable mats or single-use sheets). These mats can be altered with coloring or shape-pasting to create different terrain; they provide for movement and attack in multiple directions; and they facilitate rapid set-up and take-down. The Risk pieces with their different colors offer a basic cavalry and infantry contrast; the artillery units can be used for heavier cavalry or units like elephants or chariots. Different colors can represent separate national contingents or different types of non-cavalry (e.g. archers, peltasts, sappers).

The Activity

I asked my students to study ancient and modern examples of three battles from the campaigns of Alexander the Great (Granicus, Issus and Gaugamela). This is one of the most important steps in the process, if the students do not come prepared with knowledge of the battles, it is pretty hard to proceed.

The students were split into groups and then assigned to either Persian or Macedonian sides. Students had to collaborate in setting up the units in their appropriate numbers (proportional) and positions. Once they had agreed on positions, I asked them to try to proceed with the battle as it was described in their texts (using the rules posted below). If the gameplay did not allow them to replicate the battle, I asked them to evaluate their results and suggests new ‘rules’ that would yield the historical results. In the second day, once the students had accomplished all this, I asked them to suggest strengths and weaknesses of each side’s strategy and to propose tactics that might have affected the outcome.

I drew up a draft of the rules for gameplay beforehand based on the Risk principle of rolling multiple six-sided dice. I introduced movement rules to mimic the speed of cavalry in attack and adapted the number of dice available for attack and defense based on whether or not units were attacking or retreating and taking into consideration the advantages of cavalry over infantry. In addition and in response to student questions, we adopted rules to strengthen the Companion cavalry and infantry when they fight adjacently to another; we added a morale test to make a rout possible; and we limited the effectiveness of the archers.

The game proceeds in a basic ‘turn’ order: every unit has the option to move or attack each round of play before any given one could repeat. Cavalry can move and attack in the same turn; infantry cannot. (See rules below for full description).

The process of creating the game-rules with the students forced us all to think more deeply about terrain, tactics and unit strength. Variations for longer game play that could help illustrate other aspects of ancient warfare might include putting different contingents under the command of separate players who are not allowed to communicate.

Alexander breaks through in the Battle of Issus, with Risk pieces. pic.twitter.com/0ep6Sl9Poc

— sententiae antiquae (@sentantiq) February 26, 2015

Epiphanies

The students clearly learned a lot from the process, but some of the most important things are:

1. Ancient narrative descriptions of battles focus on dominant characters and units and often fail to describe the full field of battle. In modeling the battles, students were left to wonder what the majority of units on the field would have been doing.

2. Alexander’s tactics were aggressive, risky, and hard to duplicate in a gaming environment (without heavily changing the rules)

3. Persian starting formations were too static; and the Persians seem to have utilized too few of their overwhelming numbers.

4. Narratives of battles alone cannot convey sufficient senses of space or time (especially simultaneity). Modeling helps enormously.

Results (From Student Evaluations)

After two days of running these games, I provided students with a Questionnaire asking what they learned, what they might change and whether or not the exercise deserved to be repeated. Unanimously, students thought the exercise should be repeated because it was fun, much more helpful than merely looking at diagrams of battles, and because it sparked many enlightening and lively discussions (about differences in battle reports, uses of different troops, and the rules).

Battle of Granicus with Risk pieces. Diodorus and Arrian disagree. Archers do nothing! Dice decide all. pic.twitter.com/vMLvpOSKxB

— sententiae antiquae (@sentantiq) February 26, 2015

Students who self-reported as “kinesthetic learners” praised the tangibility of the experience and its impact not just on their understanding but on their recall. Many students reported that they had not realized how much strategy mattered or how much, at the same time, chance was important.

In addition, students had not previously understood the many small moves that make up a large engagement. Students did mention that the rules seemed a little complicated (thus warning against making them any more involved. Some students reported anxiety about how they were going to be graded—and I don’t know if the participation grade I gave everyone was sufficient to the magnitude of the undertaking.

Battle of Issus with Risk pieces: Persians win when they attack first! pic.twitter.com/Kn4lmwVgg1

— sententiae antiquae (@sentantiq) February 23, 2015

The Rules

1. Set-Up

Calvary: One unit per hex-space

Infantry: Three units per hex-space

Turn: One round of movement and attack. Cavalry and archers may move and attack in same round.

2. Movement

Calvary: 3 hex-spaces per turn (only 1 space per turn for first two turns of retreat)

2 spaces without attack across significant barriers (water, elevation)

1 space with attack across significant barriers

Infantry: 1 hex-spaces per turn (same speed in retreat)

All units may defend but not attack in retreat

If adjacent unit perishes, all units must pass MORALE roll (1d, 3 or higher); if failed, unit must retreat one hex and not attack

3. Attack/Defense

Cavalry: 5 dice against stationary infantry (defended against with 3); win tie

6 dice against retreating infantry (defended against with 1); win tie

3 dice against advancing infantry when in flight (defended against with 2); lose tie

5 dice against cavalry in engagement (defended against with 3); lose tie

6 dice against cavalry in retreat (defended against with 2); win tie

Infantry: 3 dice against attacking cavalry (if infantry is stationary); lose tie; 1 attack dice in retreat; lose tie

3 dice against retreating infantry (defended against with 2); win tie

3 dice against standing infantry (defended with 2); lose tie

1 dice against advancing infantry while retreating); lose tie

+1d defense if on elevation

Archers: 2 dice against 1 defense (win tie) within 4 hex-spaces (must roll 3+)

1 dice against 1 defense 4-5 hex spaces (must roll 3+); lose tie

1 dice against 2 defense 6-7 hex spaces (must roll 4+); lose tie

1 dice against 3 defense (7-8 hex spaces) (must roll 5+); lose tie

Move 3 spaces every two rounds in retreat

1 defense dice against any attack; lose tie

Special: Companion Cavalry and Infantry: + 1 d on attack; +1 defense; +2d for both if surrounded with allies

Chariots: +1 space movement per turn; +2d attack against infantry; 1 motionless turn to change direction

That Persian cavalry was pretty heavy with armor, slow bastards.

Yeah, we probably should have modified rules to reflect heavy vs light cavalry…

Looks like a good time and I think it would be a great way to teach the battles and strategy. I think even just having the students set it up would be instructive.

I’m sort of surprised that the war game is described here as if it’s a novelty. War games on hexagonal grids have been standard commercial products for something like 50 years. While some are extremely detailed and complicated and can take literally hundreds of hours to complete, others are comparatively simple and straightforward, including many on ancient topics.

I used to play these sorts of games when I was a teenager, and I can remember becoming conversant with the geopolitical realities of the Greek world as determined by topographer via a game called “The Conquerors”, which had a number of scenarios relating to the Hellenistic world and to the Roman conquest. So they’re good not just for studying tactics on the battlefield but also for broader strategy.

You’re right, this isn’t original at all! And I hope I didn’t give the idea that I thought it was. I know a lot of people do this vocationally and avocationally. For my students, however, it was entirely new and useful.