Source: “Vergil at Pompeii.”[1]

In the ancient city of Pompeii, the ruins are adorned with various lines from Vergil’s Aeneid, revealing an anomaly: a misspelling and the absence of word separation. While modern readers may find this puzzling, ancient Latin readers, depending on their education and social class, would have immediately noticed the misspelling and intuitively separated the words in their pronunciation of the famous line “Arma virumque cano.” This graffiti in Pompeii, summarized by classical scholar James Franklin in his article “Vergil at Pompeii: A Teacher’s Aid,” offers valuable insights into the connection between writing and reading practices. It highlights the ways in which different scripts and writing techniques shaped the technologies of reading.

The Pompeii graffiti are among the most famous examples of everyday ancient Latin script.[2] However, they vary in readability and may have been created for different reasons, including the scribbling of bored schoolboys or as commentary on social situations and advertisements for local plays or productions. Interestingly, similar to the texts of that time, the Pompeii graffiti lacked spaces between words, indicating a more significant trend in spacing and lettering in ancient Latin and other languages.

Source: “Vergil at Pompeii.”

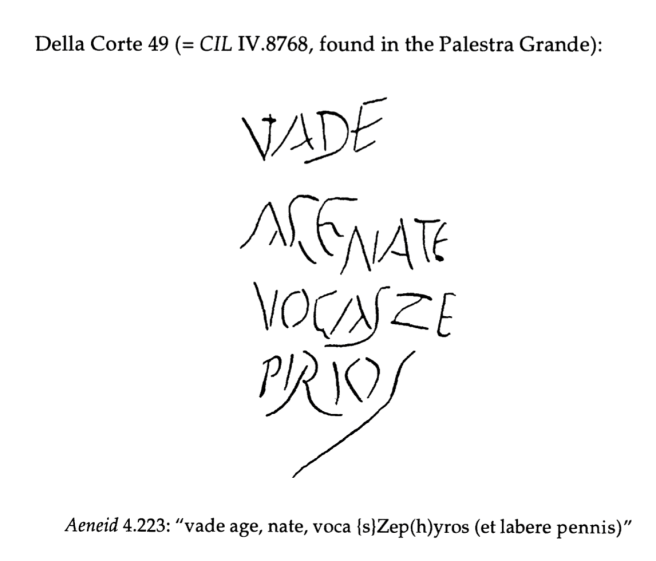

Another more ambiguous example would be this inscription, where the words are separated. The original author of this engraving knew that if the words were not distinct, then the average Roman might have confused the phrase. Even in the caption down at the bottom, the editor had to place in commas and other markers to help the English readers decipher what was written. If read without the word breaks, this small piece of poetry would have a lot more ambiguity surrounding it. “Age” and “Nate” are combined in the second line, this combination could be misconstrued as the Latin word for “advocate,” which is a different word and not what it is supposed to mean.

The absence of spaces in ancient script is a characteristic not exclusive to Latin but also found in other ancient languages, including Greek. Among the various intriguing patterns of Greek script, one that stands out is known as “boustrophedon.” The term “boustrophedon” originates from the Greek words “bous,” meaning “ox,” and “strephein,” meaning “to turn.” Thus, it translates to “turning as an ox in plowing,” a fitting name for the complex and multi-directional nature of this script.

Boustrophedon was employed during certain time periods in ancient Greece, adding a unique and fascinating dimension to the reading experience. In the early periods of Greek history, precisely during the Geometric Period (circa 9th to 8th century BCE) and the Archaic Period (circa 7th to 6th century BCE), boustrophedon script was commonly used for inscriptions on various materials, such as stone stelae and pottery.

When encountering a boustrophedon text, readers would follow a pattern reminiscent of an ox plowing a field. They began reading from the left, progressing from left to right until the end of the line. At that point, instead of continuing from left to right on the next line as one would do in modern scripts, they turned around, just like an ox at the end of a row, and read from right to left on the next line. This alternating back-and-forth directionality provided a unique challenge to readers, requiring them to adapt to a different mode of reading.

Source: “Non-Attic Greek Vase Inscriptions”[3]

Early on, Greek and Latin scripts lacked spaces or any indication to separate words, placing the burden on the reader to determine word boundaries. Beginning in the 600-700 CE, monks in northern Europe introduced spaces into the Latin texts they were studying, mirroring the spaces we see in modern books, to enhance reading speed.

Similarly, in the written form of Akkadian, distinct glyphs separated words, resembling the hieroglyphics of ancient Egyptian. Outlined boxes provided further spacing by delineated separate sentences. However, these different methods of separation present a challenge for modern researchers trying to translate these ancient texts. Without cultural context or other indications, researchers had to resort to trial and error to determine the reading direction. Eventually, it was established that Akkadian written in cuneiform should be read from left to right.

Paul Saenger, in his monograph Space Between Words: The Origins of Silent Reading, explores the writing and reading practices of ancient languages, with a focus on Latin. He traces the gradual separation of words and their connection to evolving reading practices. Saenger describes how ancient Roman scholars such as Livy (d. 17 CE)[4] used “Scriptura Continua,” a form of writing without punctuation marks, diacritics, or distinguished letter cases. Scriptura Continua created a more dramatic and theatrical reading experience but also slowed down the reading process and made comprehension difficult. Over time, Scriptura Continua gave way to the current reading system, which allows for silent reading at a faster pace. Saenger emphasizes that the absence of spaces between words in ancient texts required readers to exert more effort and engage in more eye movements to ensure accurate word separation.

In modern curriculum, Latin is taught with spaces between words, as this is what contemporary readers are accustomed to. However, it is worth noting that aristocratic students who read Latin in ancient times would have encountered texts without word spacing. They were expected to decipher the different words as part of their curriculum.

While the addition of spaces in ancient scripts has undoubtedly made reading easier, it raises the question: What might be lost when spaces are inserted? The breaking up of Scriptura Continua potentially obscures certain nuances in the text. For instance, certain lines in the Aeneid, consisting entirely of diphthongs and long syllables, were meant to be read slowly and dramatically, evoking strong and intense emotions for the reader or speaker.

When reading texts with spaces or in translation, there is always a degree of nuance lost from the original language. Much like a perfect translation does not exist, developments in script and how one reads marks a departure from the original text, making its essence nearly impossible to capture.

In conclusion, the graffiti in Pompeii and the study of ancient scripts shed light on the interplay between writing and reading practices. The absence of spaces between words in ancient Latin and other languages, such as Greek and Akkadian, required readers to possess a deep understanding of the language and context to decipher and interpret the text accurately. The gradual introduction of word spacing in Latin and the current reading system has undoubtedly made reading more efficient and accessible. However, the insertion of spaces may also obscure certain nuances and the original dramatic impact intended by the ancient authors.

Understanding the historical development of script and reading practices enhances our appreciation of ancient texts and the challenges faced by ancient readers. It reminds us that language is a dynamic and evolving system shaped by cultural and societal factors and that the conventions and norms of our time influence the way we read and interpret texts.

Hunter MacArthur is a junior at St. Sebastian’s in Needham. He can be reached at huntermac999@gmail.com

Sources

[1] James L. Franklin Jr., “Vergil at Pompeii: A Teacher’s Aid,” The Classical Journal 92(2): 1996-7, pp. 175-184. See also Kristina Milnor, Graffiti and the Literary Landscape in Roman Pompeii (Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press, 2014).

[2] Kristina Milnor, Graffiti and the Literary Landscape in Roman Pompeii (Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press, 2014).

[3] Wachter, Rudolf. Non-Attic Greek Vase Inscriptions. Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2001.

[4] Paul Saenger, Space Between Words: The Origins of Silent Reading (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2001), 5.