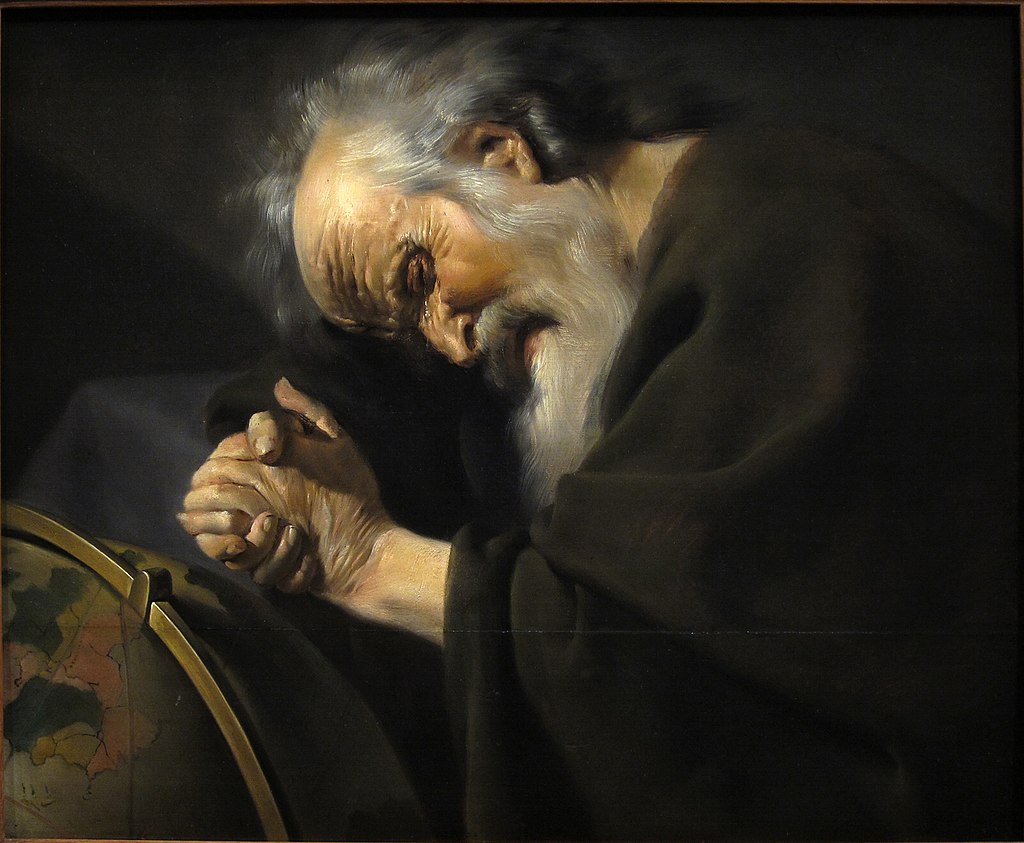

“You cannot step into the same river twice.”

δὶς ἐς τὸν αὐτὸν ποταμὸν οὐκ ἂν ἐμβαίης.

Heraclitus

There is an old anecdote about John Dryden, illustrating both his bookish ways and his casual and malicious disregard for his wife:

Dryden himself told us that he was of a grave cast and did not much excel in sallies of humour. One of his bon mots, however, has been preserved. He does not seem to have lived on very amicable terms with his wife, Lady Elizabeth, whom, if we may believe the lampoons of the time, he was compelled by one of her brothers to marry. Thinking herself neglected by the bard, and that he spent too much time in his study, she one day exclaimed, ‘Lord, Mr. Dryden, how can you always be poring over those musty books? I wish I were a book, and then I should have more of your company.’ ‘Pray, my dear,’ replied old John, ‘if you do become a book let it be an almanack, for then I shall change you every year.’ [Oxford Book of Literary Anecdotes, p.49]

As I considered telling my students this anecdote, I realized that while the reference to Dryden was likely to be incomprehensible to them, the joke itself would fall flat because they likely do not know what an almanac is. (Lest this seem too much of a stretch for my readers who do not work with teenagers, many of these students cannot tell time on an analog clock, have no knowledge of Roman numerals, and get entirely stumped by lexical curiosities such as pejorative or gubernatorial.)

The almanac is today both charmingly obsolete and quaint to the point of absurdity. To be sure, I have seen The Old Farmer’s Almanac for sale in the check-out lane at the hardware store every year, but I could not imagine people purchasing them for serious consultation. Nevertheless, I find that a fair number of online reviews for the 2020 edition of The Old Farmer’s Almanac combine a curious enthusiasm for its outmoded practicality with a sentimental nostalgia about the publication’s venerable old age.

Obsolescence occurs in two ways. The first may be readily observed in the world of classical scholarship by the rapid obsolescence of traditional dictionaries. Though I wrote before of my own tendency to fetishize the dictionary as a physical object, I nevertheless rarely use a physical lexicon anymore because I find Logeion so powerful and effective. But electronic lexical resources have not made dictionaries themselves obsolete – merely their physical forms. An online dictionary may aggregate entries from various lexica, but the basic premise of recording the definitions and uses of individual words in one place, used as a reference, remains fundamentally the same.

A more profound form of obsolescence occurs when the world itself changes in such a way as to make something wholly irrelevant or useless. Phone books, and even publicly available phone directories, are no longer necessary in an age of cheap web hosting, constant internet access, and efficient search engines; moreover, the evanescence and rapid mutability of cell phone numbers would render such a directory entirely unmanageable. Indeed, one need not be surprised that the Terminator, in the 1984 film of that name, was unable to kill Sara Connor – it looked her up in a phone book. Did the AI which orchestrated human extinction really have no better way of seeking her out? At any rate, it is clear enough that our timeline diverged sharply from that imagined future, since we have been treated to an endless string of increasingly horrible sequels, revealing that Skynet’s plan was actually just to bore us to death.

Occasionally I hear authors and critics speculate (usually with some show of ambivalent feeling) about the end of literary fiction. Closer to home, I know that it is fashionable to speculate about the end of Classics. The sense, in both cases, is that neither of these disciplines is particularly suited to a rapidly changing world, in which the memeification of culture has rendered attention, critical thought, and even history itself apparently irrelevant. My own students have told me that they would much rather spend ten seconds fully absorbing a post on Instagram than reading a book, because it is so “short and to the point.” I suppose that one cannot blame them, considering that the orange, suppurating mass which currently fills out a suit and a chair in the White House has bragged about his entire estrangement from books, which he thinks could be much more readily digested as sound-bite summaries.

Tweets and Instagram posts may be “short and to the point,” but so are aphorisms and epigrams. Nevertheless, I don’t see that anyone is lining up to buy copies of Martial. The appeal of these social media is not their brevity, as is made clear by the fact that no one reads old posts with any enthusiasm or fervor. Rather, social media creates a kind of Heraclitean horror show – an ever fluid and dynamic present in which we cannot even step into the same river once. In truth, nothing good actually happens on the internet, but I like many people often find myself transfixed, refreshing for the latest updates, most of which I gloss over entirely. This frenzied update and consumption cycle not only produces the impression that events in our world are occurring more rapidly than they used to, but also causes them to occur at a more rapid rate. News does not become obsolete because a story has been fully investigated or dealt with. Rather, it becomes obsolete because the very act of engaging with the news on social media (especially if it is powerful people who are engaging with it) in itself triggers more news. Even apparently “timeless” content like photos of cute dogs or silly cats has an internet shelf life of a day at the most. All of those dog videos just washed along by the endless stream of other dog videos.

To return to the outmoded almanac. While it would be tempting to say that these manuals have undergone the first kind of obsolescence thanks to real-time weather updates accessible on the internet, it is unfortunately the case that they have fallen victim just as much to the second form of obsolescence, in which the rapidly changing patterns of our planet’s climate have rendered traditional wisdom and climactic prognostication largely futile. Much the same can be said of traditional punditry. In an age of chaos, it seems frightfully masturbatory and absurd to sit behind a glass desk and deliver Pythian proclamations about the political landscape of next year when the entire geopolitical landscape is drastically altered every few hours, usually in response to something posted on a certain someone’s social media feed.

An old friend of mine used to say that he considered all literature published before the 20th century irrelevant. As repugnant as I found the notion, I could see that he had some point. Virginia Woolf once observed that, ”on or about December 1910 human character changed,” and a facile reading of the classics (whether construed as the Greek and Roman canon or old books more generally) may suggest that they have little to offer to someone after trench warfare, the Holocaust, the nuclear arms race, or any of the other horrors of the 20th century. If some of the horrors of the 21st seem less blatantly aggressive and horrific than those of the 20th, it may be because our passive acceptance of and complicity in them renders them so much harder to confront honestly. Yet it is perhaps because of the new existential horror of these two centuries that our older literature will not be rendered obsolete. As a classic example, Jonathan Shay’s Achilles in Vietnam draws on Homer to make sense of PTSD. One of my professors once sold his Greek and Roman civilization courses by arguing that anyone who had read ancient history could open the newspaper any day and say, “I’ve seen this bullshit before.”

But the chief value of literature (old and new) is its ability to allow us to engage with what is human. Ostensibly, social media presents us with our most human selves, but really it just aggregates a pullulating mass of swollen id shouting into the vacuous ether of a present which has already been lost. In a curious way, constant engagement with the present is the firmest assurance that we will never experience the present at all. Rather, a meaningful engagement with all of human experience – including its past, even or especially when mediated through the artificiality of literature – is essential to making sense of an accelerating and vanishing present.

People used to change their almanacs out every year, and the malice of Dryden’s joke is his suggestion that he would do the same to a person. Yet this is, in effect, what we do both to our culture and the people with whom we interact. I have inadvertently jettisoned a number of friends from my life by first turning them into social media correspondents and then simply forgetting to put in the minimal and largely passive effort of “keeping in touch.” So, too, relating with people personally or “IRL” has in some sense degenerated to friends asking each other whether they had seen the latest thing online. From Descartes on, philosophers were terrified by the fact that we have no immediate access to reality; in the 21st century, we have responded to this terror by adding new layers of mediation to it, which may explain why it all feels so unreal.

This is not meant as a manifesto, or a rallying cry for Classics, or even for literature more generally. Despite the apparently strident and indignant tone of what may be observed above, this screed ends with something in the old confessional mode. I find myself every day drawn more and more by the Siren song of nostalgia. Indeed, I find the continued viability of a published Farmer’s Almanac not just charming, but somehow deeply comforting. Reading actual books feels better as media update faster; older films and even old television attract me far more as YouTube gets better at predicting what kinds of mindless and insipid trash might seize my attention for a few minutes; and as the very idea of civilization seems to be collapsing into the dark and abysmal nullity of hypercapitalist moral and intellectual corruption, it is nice to remember that human civilization was once a thing, and that for all of its problems it occasionally produced things which were poignant or profound or beautiful. By the time we feel it, our step into the river has already been taken, but we can pause for a moment and watch as the water rushes on.

There are many moments of poignance and pertinence here, but this is poetic:

“I suppose that one cannot blame them, considering that the orange, suppurating mass which currently fills out a suit and a chair in the White House has bragged about his entire estrangement from books, which he thinks could be much more readily digested as sound-bite summaries.”

Every day that I feel my contempt for that vile little worm can surely grow no more, it grows nevertheless. But I have come to see him as emblematic not just of political evil and dysfunction, but of the greater failures of our culture as a whole.

“One of my professors once sold his Greek and Roman civilization courses by arguing that anyone who had read ancient history could open the newspaper any day and say, ‘I’ve seen this bullshit before.’”

What do you mean, “open a newspaper” ?

To be sure, it’s almost as outdated a reference as “professor” or “reading”!

‘horrorshow’ from Burgess (Clockwork Orange) derived from Russian ‘harasho’ for something good, though we commonly misuse it to mean horrible, I guess thinking of horror movie, or horror v show maybe?