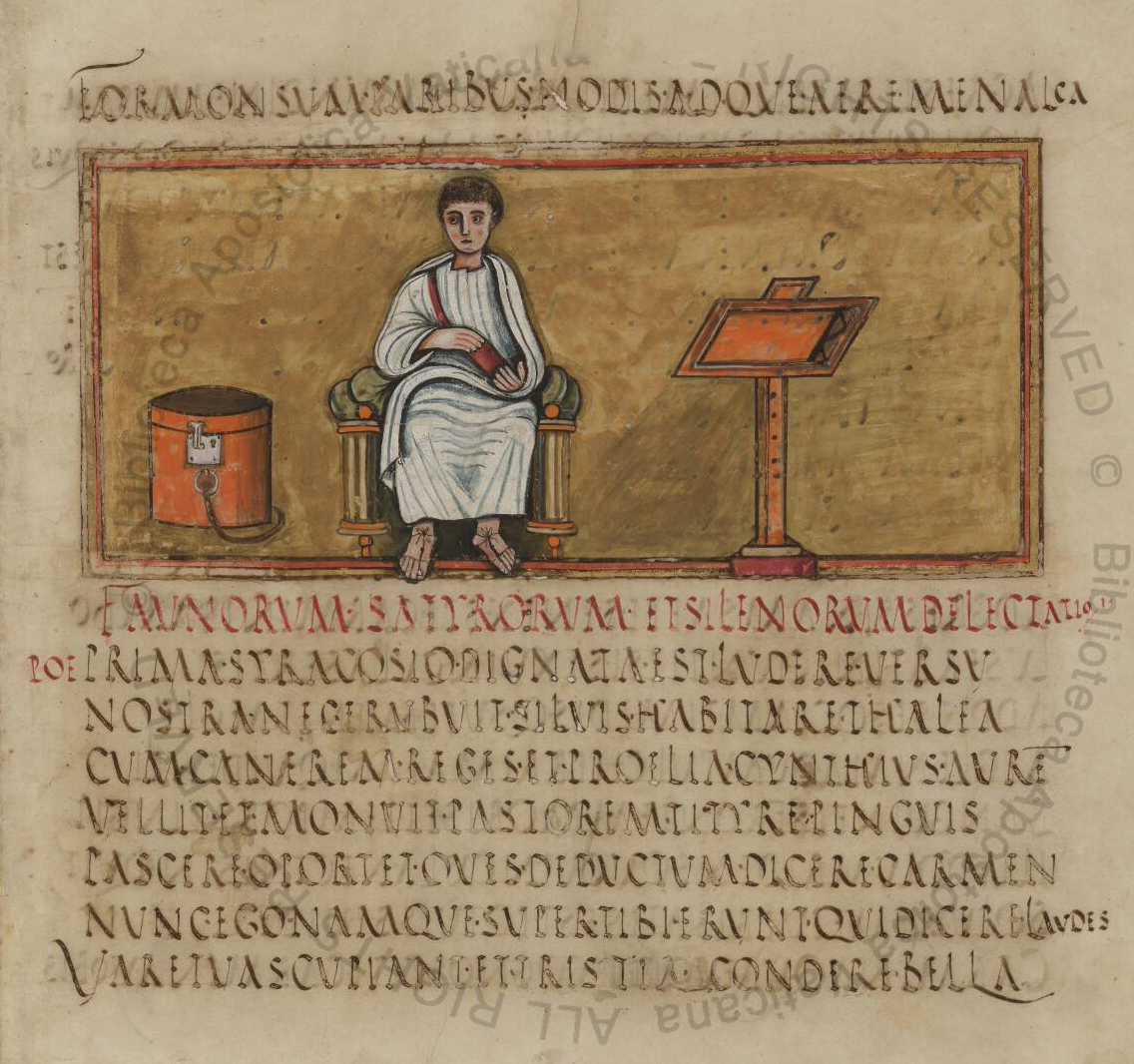

Aeneas Silvius Piccolomini, de Liberorum Educatione, chp. 69

“A teacher should prefer Vergil above all other poets, since his eloquence and glory are so great, that they could be neither increased by anyone’s praises nor diminished by anyone’s censure.”

Inter heroicos Vergilium cunctis praeferat, cuius tanta eloquentia est, tanta gloria, ut nullius laudibus crescere, nullius vituperatione minui possit.

Donatus, Vita Vergilii

“Asconius Pedianus wrote a book against Vergil’s detractors, but he nevertheless adds some objections of his own, mostly dealing with Vergil’s narration and the fact that he had taken much from Homer. But he also says that Vergil was accustomed to refute this latter criticism thus: ‘Why did they themselves not try to do take some verses from Homer? To be sure, they would learn that it easier to take Hercules’ club than to lift a verse from Homer.’ Yet, Asconius adds that he decided to retire so that he could do everything to the satisfaction of his malicious critics.”

Asconius Pedianus libro, quem contra obtrectatores Vergiliis scripsit, pauca admodum obiecta ei proponit eaque circa historiam fere et quod pleraque ab Homero sumpsisset; sed hoc ipsum crimen sic defendere adsuetum ait: cur non illi quoque eadem furta temptarent? Verum intellecturos facilius esse Herculi clavam quam Homero versum subripere”; et tamen destinasse secedere ut omnia ad satietatem malevolorum decideret.

Macrobius, Saturnalia 6.2

“I fear that, in my eagerness to show how much Vergil accomplished from his reading of the ancients, and what blossoms and what ornaments he poured forth from all of them into his own poetry, I may accidentally offer an opportunity for criticism to those uncultured and malignant fools who censure such a man for his usurpation of other’s works, not considering that this is the fruit of reading: to imitate those things which you approve in others, and to turn the sayings of others which you marvel at into your own use by a fitting turn. Our poets have done this among themselves, just as much as the best of the Greeks did. And, to avoid talk of foreign precedent, I could show with numerous examples how much the authors of our ancient canon have lifted from one another.”

Etsi vereor me, dum ostendere cupio quantum Virgilius noster ex antiquiorum lectione profecerit et quos ex omnibus flores vel quae in carminis sui decorem ex diversis ornamenta libaverit, occasionem reprehendendi vel inperitis vel malignis ministrem, exprobrantibus tanto viro alieni usurpationem, nec considerantibus hunc esse fructum legendi, aemulari ea quae in aliis probes et quae maxime inter aliorum dicta mireris in aliquem usum tuum oportuna derivatione convertere, quod et nostri tam inter se quam a Graecis et Graecorum excellentes inter se saepe fecerunt. Et, ut de alienigenis taceam, possem pluribus edocere quantum se mutuo conpilarint bibliothecae veteris auctores.

Vergil, Aeneid 2.796-798

“And here, I was shocked to find an overwhelming

Flood of new companions, mothers and men,

A band assembled for exile, a pitiable crowd.”

“Atque hic ingentem comitum adfluxisse novorum

invenio admirans numerum, matresque virosque,

collectam exsilio pubem, miserabile vulgus.