Epitaphios: A speech performed annually in honor of those who have died in war. The most famous that remains is Thucydides’ version of Perikles’ funeral oration (2.35-46).

Thucydides, 2.35

“Many of those who have spoken here already praised the one who made this speech law, that it is a noble thing to speak over the burials of those who died in war. But honors paid in deeds for deeds performed by good men would seem to be sufficient to me—the acts which you see performed now by the public at this burial. The virtues of many should not be risked by entrusting them to the good or poor speaking of one man alone. For it is hard to speak reasonably on something upon which faith in the truth is only partly firm.

For the one who knows the story and is a well-informed listener may take it rather harshly compared to what he wants, knows and believes should be said. Someone inexperienced of the events may find fault because of envy if he hears anything behind his own nature. For praise spoken of others is endurable only to the point that each person believes that he is capable of achieving what he has heard. People envy and disbelieve those who surpass them.

But since it was believed noble to do these things by our forefathers, it is right that I follow the law and try as much as possible to fulfill each of your desire and expectation.”

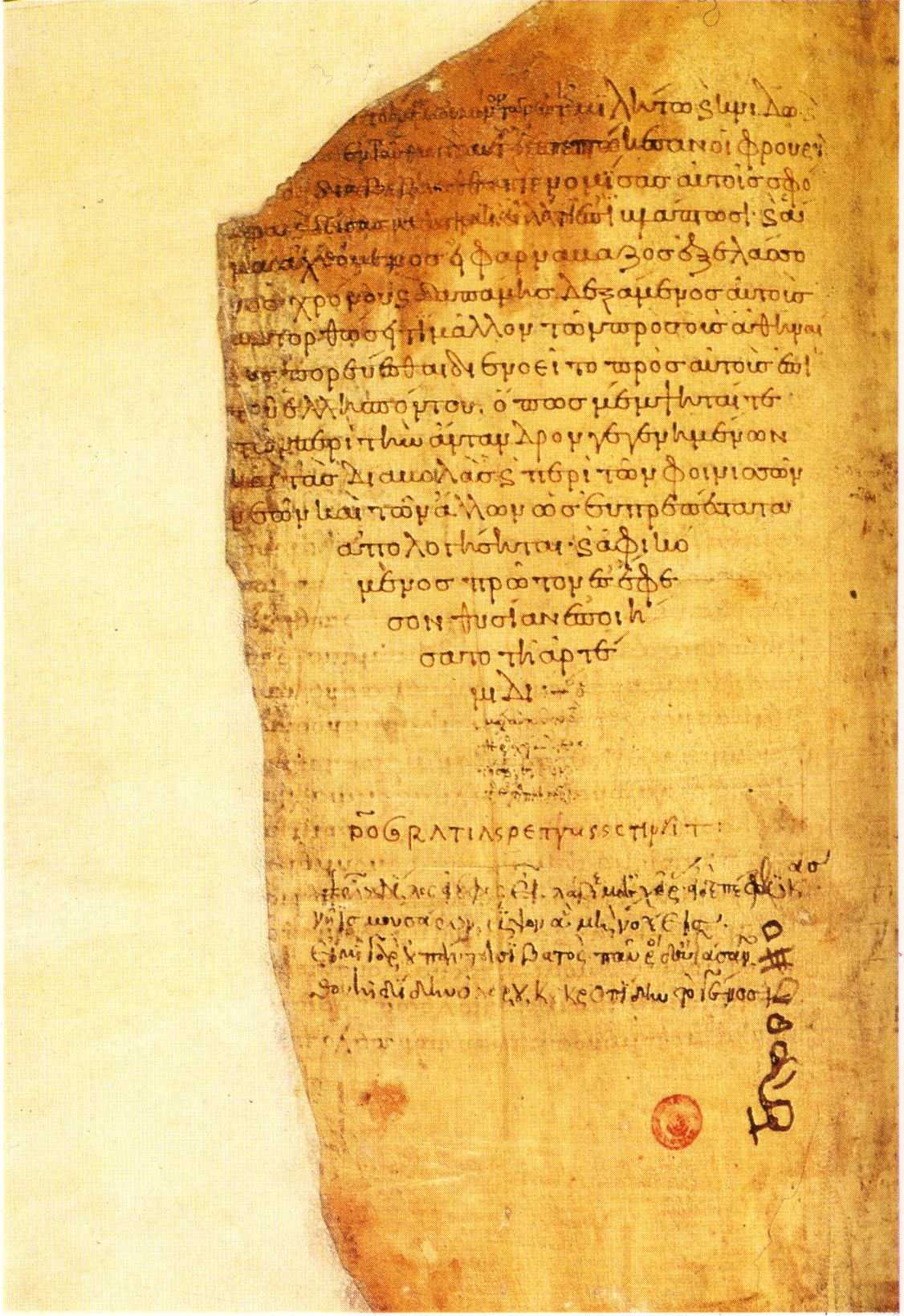

‘Οἱ μὲν πολλοὶ τῶν ἐνθάδε ἤδη εἰρηκότων ἐπαινοῦσι τὸν προσθέντα τῷ νόμῳ τὸν λόγον τόνδε, ὡς καλὸν ἐπὶ τοῖς ἐκ τῶν πολέμων θαπτομένοις ἀγορεύεσθαι αὐτόν. ἐμοὶ δὲ ἀρκοῦν ἂν ἐδόκει εἶναι ἀνδρῶν ἀγαθῶν ἔργῳ γενομένων ἔργῳ καὶ δηλοῦσθαι τὰς τιμάς, οἷα καὶ νῦν περὶ τὸν τάφον τόνδε δημοσίᾳ παρασκευασθέντα ὁρᾶτε, καὶ μὴ ἐν ἑνὶ ἀνδρὶ πολλῶν ἀρετὰς κινδυνεύεσθαι εὖ τε καὶ χεῖρον εἰπόντι πιστευθῆναι. χαλεπὸν γὰρ τὸ μετρίως εἰπεῖν ἐν ᾧ μόλις καὶ ἡ δόκησις τῆς ἀληθείας βεβαιοῦται. ὅ τε γὰρ ξυνειδὼς καὶ εὔνους ἀκροατὴς τάχ’ ἄν τι ἐνδεεστέρως πρὸς ἃ βούλεταί τε καὶ ἐπίσταται νομίσειε δηλοῦσθαι, ὅ τε ἄπειρος ἔστιν ἃ καὶ πλεονάζεσθαι, διὰ φθόνον, εἴ τι ὑπὲρ τὴν αὑτοῦ φύσιν ἀκούοι. μέχρι γὰρ τοῦδε ἀνεκτοὶ οἱ ἔπαινοί εἰσι περὶ ἑτέρων λεγόμενοι, ἐς ὅσον ἂν καὶ αὐτὸς ἕκαστος οἴηται ἱκανὸς εἶναι δρᾶσαί τι ὧν ἤκουσεν· τῷ δὲ ὑπερβάλλοντι αὐτῶν φθονοῦντες ἤδη καὶ ἀπιστοῦσιν. ἐπειδὴ δὲ τοῖς πάλαι οὕτως ἐδοκιμάσθη ταῦτα καλῶς ἔχειν, χρὴ καὶ ἐμὲ ἑπόμενον τῷ νόμῳ πειρᾶσθαι ὑμῶν τῆς ἑκάστου βουλήσεώς τε καὶ δόξης τυχεῖν ὡς ἐπὶ πλεῖστον.

Lysias, Epitaphios 1-3

“If I believed it were possible, men in attendance, to make clear in this speech the virtue of the men who lie buried here, I would complain to those who summoned me to speak with only a few days’ notice. But since the whole of time would not be enough for all men together to prepare a speech worthy of these deeds, for this reason the city seems to take pity on those who speak here in making their assignment late–since it knows that the speakers will have the pardon of their audiences.

Yet, though my speech is about those men, my struggle is not with their deeds but with those who have spoken for them before. For their virtue has provided such an abundance both in those able to compose poetry and those who are selected to speak, that even though many fine things have been said about them by my predecessors and many other things have been omitted by them, it is still the case that enough remains for those who follow them to say. For there is no land or sea unknown by these men; and in every direction among all peoples even those who suffered at their hands sing their praises.

First, therefore, I will recite the ancient trials of our forefathers, procuring for us a reminder from their fame. For it is right for all men to remember them, praising them in songs and recalling their names in the praise of good men, honoring them on occasions such as this, and teaching the living through the deeds of the dead.”

Εἰ μὲν ἡγούμην οἷόν τε εἶναι, ὦ ἄνδρες οἱ παρόντες ἐπὶ τῷδε τῷ τάφῳ, λόγῳ δηλῶσαι τὴν τῶν ἐνθάδε κειμένων [ἀνδρῶν] ἀρετήν, ἐμεμψάμην ἂν τοῖς ἐπαγγείλασιν ἐπ’ αὐτοῖς ἐξ ὀλίγων ἡμερῶν λέγειν· ἐπειδὴ δὲ πᾶσιν ἀνθρώποις ὁ πᾶς χρόνος οὐχ ἱκανὸς λόγον ἴσον παρασκευάσαι τοῖς τούτων ἔργοις, διὰ τοῦτο καὶ ἡ πόλις μοι δοκεῖ, προνοουμένη τῶν ἐνθάδε λεγόντων, ἐξ ὀλίγου τὴν πρόσταξιν ποιεῖσθαι, ἡγουμένη οὕτως ἂν μάλιστα συγγνώμης αὐτοὺς παρὰ τῶν ἀκουσάντων τυγχάνειν. ὅμως δὲ ὁ μὲν λόγος μοι περὶ τούτων, ὁ δ’ ἀγὼν οὐ πρὸς τὰ τούτων ἔργα ἀλλὰ πρὸς τοὺς πρότερον ἐπ’ αὐτοῖς εἰρηκότας. τοσαύτην γὰρ ἀφθονίαν παρεσκεύασεν ἡ τούτων ἀρετὴ καὶ τοῖς ποιεῖν δυναμένοις καὶ τοῖς εἰπεῖν βουληθεῖσιν, ὥστε καλὰ μὲν πολλὰ τοῖς προτέροις περὶ αὐτῶν εἰρῆσθαι, πολλὰ δὲ καὶ ἐκείνοις παραλελεῖφθαι, ἱκανὰ δὲ καὶ τοῖς ἐπιγιγνομένοις ἐξεῖναι εἰπεῖν·οὔτε γὰρ γῆς ἄπειροι οὔτε θαλάττης οὐδεμιᾶς, πανταχῇ δὲ καὶ παρὰ πᾶσιν ἀνθρώποις οἱ τὰ αὑτῶν πενθοῦντες κακὰ τὰς τούτων ἀρετὰς ὑμνοῦσι.

Πρῶτον μὲν οὖν τοὺς παλαιοὺς κινδύνους τῶν προγόνων δίειμι, μνήμην παρὰ τῆς φήμης λαβών· ἄξιον γὰρ πᾶσιν ἀνθρώποις κἀκείνων μεμνῆσθαι, ὑμνοῦντας μὲν ἐν ταῖς ᾠδαῖς, λέγοντας δ’ ἐν τοῖς τῶν ἀγαθῶν ἐγκωμίοις, τιμῶντας δ’ ἐν τοῖς καιροῖς τοῖς τοιούτοις, παιδεύοντας δ’ ἐν τοῖς τῶν τεθνεώτων ἔργοις τοὺς ζῶντας.

In Plato’s Menexenus (236dff), Socrates recites an epitaphios given by Aspasia:

“In deed, these men have what is required for them materially—now that they have obtained it, they proceed along the fated path: they have been carried out in common by the city and in private by their families. But in speech it is necessary to pay out the remaining rite which custom assigns us. For, when deeds have been performed well, memory and glory come from the audience through a speech nobly spoken. Whoever will praise the dead rightly and advise the living favorably needs this type of speech: calling upon progeny and brothers to imitate their virtue and assuaging their parents and any elders they have left behind.

What sort of speech would this seem like for us? Should we begin correctly by praising them as good men who while alive impressed their friends with their virtue and who exchanged their death for the safety of the survivors? It seems right to me to praise them in the order of nature, how they became good men. They were good men because they came from good men. So first, let us praise their families, then the way they were raised and trained. And then we will show the character of their deeds, how they proved themselves to be noble and worthy.”

῎Εργῳ μὲν ἡμῖν οἵδε ἔχουσιν τὰ προσήκοντα σφίσιν αὐτοῖς, ὧν τυχόντες πορεύονται τὴν εἱμαρμένην πορείαν, προπεμφθέντες κοινῇ μὲν ὑπὸ τῆς πόλεως, ἰδίᾳ δὲ ὑπὸ τῶν οἰκείων· λόγῳ δὲ δὴ τὸν λειπόμενον κόσμον ὅ τε νόμος προστάττει ἀποδοῦναι τοῖς ἀνδράσιν καὶ χρή. ἔργων γὰρ εὖ πραχθέντων λόγῳ καλῶς ῥηθέντι μνήμη καὶ κόσμος τοῖς πράξασι γίγνεται παρὰ τῶν ἀκουσάντων· δεῖ δὴ τοιούτου τινὸς λόγου ὅστις τοὺς μὲν τετελευτηκότας ἱκανῶς ἐπαινέσεται, τοῖς δὲ ζῶσιν εὐμενῶς παραινέσεται, ἐκγόνοις μὲν καὶ ἀδελφοῖς μιμεῖσθαι τὴν τῶνδε ἀρετὴν παρακελευόμενος, πατέρας δὲ καὶ μητέρας καὶ εἴ τινες τῶν ἄνωθεν ἔτι προγόνων λείπονται, τούτους δὲ παραμυθούμενος.

τίς οὖν ἂν ἡμῖν τοιοῦτος λόγος φανείη; ἢ πόθεν ἂν ὀρθῶς ἀρξαίμεθα ἄνδρας ἀγαθοὺς ἐπαινοῦντες, οἳ ζῶντές τε τοὺς ἑαυτῶν ηὔφραινον δι’ ἀρετήν, καὶ τὴν τελευτὴν ἀντὶ τῆς τῶν ζώντων σωτηρίας ἠλλάξαντο; δοκεῖ μοι χρῆναι κατὰ φύσιν, ὥσπερ ἀγαθοὶ ἐγένοντο, οὕτω καὶ ἐπαινεῖν αὐτούς. ἀγαθοὶ δὲ ἐγένοντο διὰ τὸ φῦναι ἐξ ἀγαθῶν. τὴν εὐγένειαν οὖν πρῶτον αὐτῶν ἐγκωμιάζωμεν, δεύτερον δὲ τροφήν τε καὶ παιδείαν· ἐπὶ δὲ τούτοις τὴν τῶν ἔργων πρᾶξιν ἐπιδείξωμεν, ὡς καλὴν καὶ ἀξίαν τούτων ἀπεφήναντο.

Demosthenes, Epitaphios (speech 60)

“Since it seems right to the state to bury those lying in this grave publicly because they proved themselves noble in war and it has been assigned to me to deliver the customary speech on their behalf, I immediately began to examine how others have crafted the appropriate praise. But while I was considering and examining this, I realized that speaking worthily of the dead is one of those things that is impossible for men. For because they have abandoned that desire to live that is natural to all men and they have decided to die well rather than continue living and watch Greece fare badly, how have they not left behind an accomplishment beyond the expression of any speech?

But, nevertheless, it seems right to me to speak the way those who have spoken here before. How serious our city is about those who have died in war is can be seen from other affairs and especially from this law by which someone is selected who will speak over the public burial. For, since we know that among noble men the possession of money and the acquisition of pleasures in life are dismissed and that they have a great desire for virtue and praise, so that they might gain these things especially, we have thought it right to honor them so that what good repute they acquired while living, might also be granted to them even now that they are dead.

If I saw that courage alone was sufficient of those traits that lead to virtue, I would praise that and forget the rest of my speech. But because it is true that they were born nobly, educated prudently, and lived honorably—all reasons they were eager to act rightly—I would be ashamed if I moved on without saying something about these things. So I will start from the beginning of their ancestry.”

᾿Επειδὴ τοὺς ἐν τῷδε τῷ τάφῳ κειμένους, ἄνδρας ἀγαθοὺς ἐν τῷ πολέμῳ γεγονότας, ἔδοξεν τῇ πόλει δημοσίᾳ θάπτειν καὶ προσέταξεν ἐμοὶ τὸν νομιζόμενον λόγον εἰπεῖν ἐπ’ αὐτοῖς, ἐσκόπουν μὲν εὐθὺς ὅπως τοῦ προσήκοντος ἐπαίνου τεύξονται, ἐξετάζων δὲ καὶ σκοπῶν ἀξίως εἰπεῖν τῶν τετελευτηκότων ἕν τι τῶν ἀδυνάτων ηὕρισκον ὄν. οἳ γὰρ τὴν ὑπάρχουσαν πᾶσιν ἔμφυτον τοῦ ζῆν ὑπερεῖδον ἐπιθυμίαν, καὶ τελευτῆσαι καλῶς μᾶλλον ἠβουλήθησαν ἢ ζῶντες τὴν ῾Ελλάδ’ ἰδεῖν ἀτυχοῦσαν, πῶς οὐκ ἀνυπέρβλητον παντὶ λόγῳ τὴν αὑτῶν ἀρετὴν καταλελοίπασιν;

ὁμοίως μέντοι διαλεχθῆναι τοῖς πρότερόν ποτ’ εἰρηκόσιν ἐνθάδ’ εἶναι μοι δοκεῖ. ὡς μὲν οὖν ἡ πόλις σπουδάζει περὶ τοὺς ἐν τῷ πολέμῳ τελευτῶντας, ἔκ τε τῶν ἄλλων ἔστιν ἰδεῖν καὶ μάλιστ’ ἐκ τοῦδε τοῦ νόμου, καθ’ ὃν αἱρεῖται τὸν ἐροῦντ’ ἐπὶ ταῖς δημοσίαις ταφαῖς· εἰδυῖα γὰρ παρὰ τοῖς ἀγαθοῖς ἀνδράσιν τὰς μὲν τῶν χρημάτων κτήσεις καὶ τῶν κατὰ τὸν βίον ἡδονῶν ἀπολαύσεις ὑπερεωραμένας, τῆς δ’ ἀρετῆς καὶ τῶν ἐπαίνων πᾶσαν τὴν ἐπιθυμίαν οὖσαν, ἐξ ὧν ταῦτ’ ἂν αὐτοῖς μάλιστα γένοιτο λόγων, τούτοις ᾠήθησαν δεῖν αὐτοὺς τιμᾶν, ἵν’ ἣν ζῶντες ἐκτήσαντ’ εὐδοξίαν, αὕτη καὶ τετελευτηκόσιν αὐτοῖς ἀποδοθείη.

εἰ μὲν οὖν τὴν ἀνδρείαν μόνον αὐτοῖς τῶν εἰς ἀρετὴν ἀνηκόντων ὑπάρχουσαν ἑώρων, ταύτην ἂν ἐπαινέσας ἀπηλλαττόμην τῶν λοιπῶν· ἐπειδὴ δὲ καὶ γεγενῆσθαι καλῶς καὶ πεπαιδεῦσθαι σωφρόνως καὶ βεβιωκέναι φιλοτίμως συμβέβηκεν αὐτοῖς, ἐξ ὧν εἰκότως ἦσαν σπουδαῖοι, αἰσχυνοίμην ἂν εἴ τι τούτων φανείην παραλιπών. ἄρξομαι δ’ ἀπὸ τῆς τοῦ γένους αὐτῶν ἀρχῆς.

Like this:

Like Loading...

This image also spoke to my book’s subject matter: namely, the idea of contest (agōn) and its representation in ancient Greek literature. In truth, I had a hard time finding an image that worked for me. I wanted some kind of ancient Greek artistic representation; perhaps because it was my first book (the “book of the thesis”), I felt it needed to be unambiguously classical. It should have been easy, right, to find an image from the whole corpus of ancient Greek ceramics, right? Wrong. I could find none of the scenes of debate in epic, history and tragedy, which were the core focus of my argument, that had been illustrated, not even—as one may have expected—the quarrel between Achilles and Agamemnon that starts off the Iliad with such a bang. There is a fresco, highly fragmented, from Pompeii’s House of the Dioscuri (on exhibition at the National Archaeological museum in Naples), which shows Achilles going for his sword; and of course there are later Renaissance paintings depicting the quarrel (such as Giovanni Battista Gaulli’s baroque rendering). But I could find none from the world of ancient Greek ceramics or friezes—perhaps because, as Robin Osborne pointed out to me, Greek artists simply were less interested in illustrating literary stories than in creating their own. (It is striking that the wall paintings from Pompeii *do* look like illustrations of early Greek literary narratives, including the moment Euripides’s Medea ponders killing her children.) What Exekias’s scene of gaming heroes gave me was a hint not only of the formalisation of contest, but also of the prominence of Achilles (who in my argument institutionalises contest in the arena of debate) and, moreover, of his pairing with Ajax (whose story in Sophocles’s tragedy formed one of my chapters).

This image also spoke to my book’s subject matter: namely, the idea of contest (agōn) and its representation in ancient Greek literature. In truth, I had a hard time finding an image that worked for me. I wanted some kind of ancient Greek artistic representation; perhaps because it was my first book (the “book of the thesis”), I felt it needed to be unambiguously classical. It should have been easy, right, to find an image from the whole corpus of ancient Greek ceramics, right? Wrong. I could find none of the scenes of debate in epic, history and tragedy, which were the core focus of my argument, that had been illustrated, not even—as one may have expected—the quarrel between Achilles and Agamemnon that starts off the Iliad with such a bang. There is a fresco, highly fragmented, from Pompeii’s House of the Dioscuri (on exhibition at the National Archaeological museum in Naples), which shows Achilles going for his sword; and of course there are later Renaissance paintings depicting the quarrel (such as Giovanni Battista Gaulli’s baroque rendering). But I could find none from the world of ancient Greek ceramics or friezes—perhaps because, as Robin Osborne pointed out to me, Greek artists simply were less interested in illustrating literary stories than in creating their own. (It is striking that the wall paintings from Pompeii *do* look like illustrations of early Greek literary narratives, including the moment Euripides’s Medea ponders killing her children.) What Exekias’s scene of gaming heroes gave me was a hint not only of the formalisation of contest, but also of the prominence of Achilles (who in my argument institutionalises contest in the arena of debate) and, moreover, of his pairing with Ajax (whose story in Sophocles’s tragedy formed one of my chapters).

The book derived from an interdisciplinary project that I had led called

The book derived from an interdisciplinary project that I had led called