Phaedrus, Fabulae 4.23

“A person of learning always has wealth on their own.

Simonides, who wrote exceptional lyric poems,

Thanks to this, lived more easily with poverty

He began to go around Asia’s noble cities

Singing the praise of victors for a set price.

Once he had done this to make a wealthier life

He planned to make a seaward journey home.

For it was on Ceos people claim he was born.

He climbed aboard a ship which an awful storm

And its advanced age caused to break apart in the sea.

Some grabbed their money-belts, others their valuable things,

Safeguards for their life. A rather curious man asked

“Simonides, you are saving none of your riches?”

He responded, “Everything that is mine is with me”

Few swam free, because most died weighed down by a drowning burden.

Then thieves arrived and seized whatever each man carried.

They left them naked. By chance, Clazomenae, that ancient city,

Was nearby. The shipwrecked men went that way.

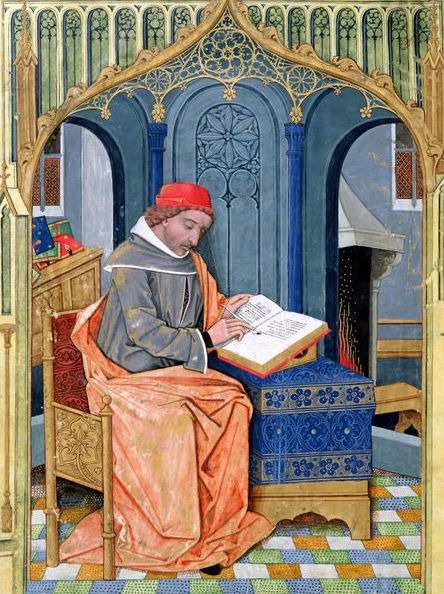

There lived a man obsessed with the pursuit of poetry

Who had often read the poems of Simonides,

He was his greatest distant admirer.

Once he recognized Simonides from his speech alone

He greedily brought him home, and decorated him

With clothes, money, servants. The rest were carrying

Signs asking for food. When Simonides by chance

Would see these men he reported “I said that all my things

Were with me: and you lost everything you took.”

Homo doctus in se semper divitias habet.

Simonides, qui scripsit egregium melos,

quo paupertatem sustineret facilius,

circum ire coepit urbes Asiae nobiles,

mercede accepta laudem victorum canens.

Hoc genere quaestus postquam locuples factus est,

redire in patriam voluit cursu pelagio;

erat autem, ut aiunt, natus in Cia insula.

ascendit navem; quam tempestas horrida

simul et vetustas medio dissolvit mari.

Hi zonas, illi res pretiosas colligunt,

subsidium vitae. Quidam curiosior:

“Simonide, tu ex opibus nil sumis tuis?”

“Mecum” inquit “mea sunt cuncta.”Tunc pauci enatant,

quia plures onere degravati perierant.

Praedones adsunt, rapiunt quod quisque extulit,

nudos relinquunt. Forte Clazomenae prope

antiqua fuit urbs, quam petierunt naufragi.

Hic litterarum quidam studio deditus,

Simonidis qui saepe versus legerat,

eratque absentis admirator maximus,

sermone ab ipso cognitum cupidissime

ad se recepit; veste, nummis, familia

hominem exornavit. Ceteri tabulam suam

portant, rogantes victum. Quos casu obvios

Simonides ut vidit: “Dixi” inquit “mea

mecum esse cuncta; vos quod rapuistis perit.