Simonides, fr. 6.3

“Simonides said that Hesiod is a gardener while Homer is a garland-weaver—the first planted the legends of the heroes and gods and then the second braided together them the garland of the Iliad and the Odyssey.”

Σιμωνίδης τὸν ῾Ησίοδον κηπουρὸν ἔλεγε, τὸν δὲ ῞Ομηρον στεφανηπλόκον, τὸν μὲν ὡς φυτεύσαντα τὰς περὶ θεῶν καὶ ἡρώων μυθολογίας, τὸν δὲ ὡς ἐξ αὐτῶν συμπλέξαντα τὸν᾿Ιλιάδος καὶ Οδυσσείας στέφανον.

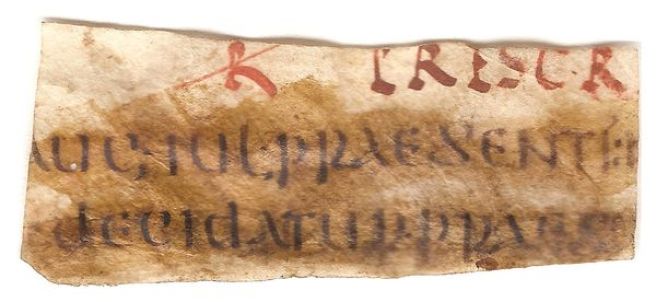

http://ica.themorgan.org/manuscript/page/98/110807

Take a minute and imagine a tree in a park or garden. Make it a really nice tree, one you’d notice and remember if you lingered on it a bit, one that has been well situated in its environment. Think about the tree’s imperfect symmetry, the way it occupies its space.

Now think about this: someone planted the tree; others tended to it and trimmed it; more people spent generations selecting this domesticated tree from its ancestral stock. Think about the uncountable hands that made this tree possible, the saplings transplanted, the varieties combined over time. What were their lives like? What stories did they tell? What were trees to them?

Then think about the tree’s beauty, its aesthetics. What makes us set this tree apart from others? What is essential about it? Our appreciation is based on other trees we might not remember as well as an entire ‘grammar’ of human beings and the environment. Like any other native language, you learned its basic syntax without trying. You have a sense of the way trees should be.

You probably judge a tree differently from a shrub for historical aesthetic reasons. You have expectations on what trees should do, how they should look, and what function they fulfill. You are mostly not cognizant of these assumptions. But you almost certainly have different notions about a shrub or a bush.

Sure, the shrub comment may seem a bit of an aside, but it is really about genre. We have different sets of expectations for different categories of form based on explicit and implicit criteria.

Now, if someone asks you who is responsible for the tree, what do you say? Is it someone who designed the park? Is it a gardener? Is it the first person who imagined a tree in the garden?

Any single answer ignores those countless hands, minds, and environments that contributed to the treeness of this tree. It also ignores the salient fact that you are the one judging the tree and that your gaze is shaped by non-tree things.

For me, the Homeric epics are like that tree. They come out of a complex relationship between performance traditions, new technologies, and aesthetics that are both products and producers of the same song culture. The reception and transformation of this ancient song culture into something fixed and reanalyzed as a text with an author has shaped our own culture too.

How we respond to ‘arboreal’ questions is keyed into individual psychology and cultural discourse. We always simplify our interpretation of where the tree came from because our minds are too small to understand we are part of mind-networks and our lives are two abbreviated to trace time’s larger sweep. We impose simple origin stories on art and human products because it is hard to escape our own single experience of culture and see how it works in the aggregate.

(for more on Homer and psychology, see my recent book The Many-Minded Man)

These individual psychologies are shaped as well by a cultural system deeply interested in teleology and the import of design. Two aspects of this among many that interest me. First, our search for meaning in the empty universe encourages us to argue that design necessitates a designer. Second, our system of values and credit under capitalism emphasizes the metaphor of authorship as an opportunity for creating and maintaining value.

The two aspects are part of a shared problem: we assign meaning to the world we see based on patterns and human-mirroring things. We re-cast the pattern as a design and in that an intention we assign to authority and authors. So group activities that result in notable patterns are reanalyzed as communications of some type of an authorial intention.

And yet, we know that meaning is made from observation and reflection.

We impose a god/author model on complex things for cultural and psychological reasons. It is a fallacy to insist that design implies a designer when we recognize design as viewers conditioned to do so. The history of Homeric scholarship and its so-called ‘question’ (of which there are actually many) is dominated by the problem of design without an urgent exploration of what design may entail until the 20th century (in addition to work by Greg Nagy (recently Homer the Pre-Classic and Homer the Classic), see Casey Dué’s recent Achilles Unbound and Barbara Graziosi’s Inventing Homer).

There’s no smoking gun about Homeric authorship. There will never be a clear answer to the issue. That we care so much about it is a problem. it is, dare I say, the rot at the core of ‘western’ liberalism and capitalism, this desperate search for ancient authority combined with a pathological need to extract profit from everything.

In searching for “Homer”, most people find what they want to find. (Something Casey Due makes the case for in looking at the invention of Ossian). My experience of teaching, reading, and writing about the epics for over two decades is that people cleave almost painfully to what they believe about authorship and art before they really listen to the Homeric poems.. That’s also why I keep returning to the bench and thinking as much about who is thinking about Homer and why.

And when I turn back I think less in terms of “who wrote the Iliad” than what the people were like who domesticated the epics and set them aside and why we still look at them today.

Plato, Ion

“For poets certainly tell us that they bring us songs by drawing from the honey-flowing springs or certain gardens and glades of the Muses just like bees. And because they too are winged, they also speak the truth.”

Λέγουσι γὰρ δήπουθεν πρὸς ἡμᾶς οἱ ποιηταί, ὅτι ἀπὸ κρηνῶν μελιρρύτων ἢ ἐκ Μουσῶν κήπων τινῶν καὶ ναπῶν δρεπόμενοι τὰ μέλη ἡμῖν φέρουσιν ὥσπερ αἱ μέλιτται. καὶ αὐτοὶ οὕτω πετόμενοι, καὶ ἀληθῆ λέγουσι.

Trees in Homer: Paris’ Ship, Odysseus’ Raft, and Laertes’ Orchards

My metaphor of a tree for seeing Homer as something organic and exhibiting aesthetic beauty without a designing authority may seem a bit whimsical, if not outlandish. But I am in part inspired by what we find in Homer. In Homeric poetry trees are objects of wealth, inheritance and memory. They appear at a crucial moment in Odysseus’ return to Ithaca when he meets his father. Odysseus follows the patterns established earlier in the book and attempts to deceive his father before they both weep and he tries to prove who he is, first by pointing to his scar, and then by pointing to the trees.

Odyssey 24. 336–339

“But, come, if I may tell you about the trees through the well-founded orchard

The ones which you gave to me—when I was a child I asked you about each

As I followed you through the garden. We traced a path through them

And you named and spoke about each one.”

εἰ δ’ ἄγε τοι καὶ δένδρε’ ἐϋκτιμένην κατ’ ἀλῳὴν

εἴπω, ἅ μοί ποτ’ ἔδωκας, ἐγὼ δ’ ᾔτευν σε ἕκαστα

παιδνὸς ἐών, κατὰ κῆπον ἐπισπόμενος· διὰ δ’ αὐτῶν

ἱκνεύμεσθα, σὺ δ’ ὠνόμασας καὶ ἔειπες ἕκαστα.

As Erich Auerbach famously observes, Odysseus’ scar is an entry-point into a universe of aesthetic thought. As I see it it, the scar is a metonym for identity and story traditions. It marks experiences and potential stories to be told. The trees are metonyms for stories themselves and they have are metapoetic as well. Alex Purves (2010:228) characterizes steps as Odysseus “taking an imaginary walk through the orchard in his mind just as [Elizabeth] Minchin has suggested that Homer takes a cognitive walk through the Peloponnese in order to recount the Catalogue of Ships (2001: 84-7).”

As Elton Barker and I explore in Homer’s Thebes (78) Whether or not Laertes’ trees mind the Iliad’s Catalogue of Ships, the trees are suggestive of the stories that are or could be told. [Cf. Henderson 1997:87 for the trees as “epic wood.” So too, “… the trees may stand metonymically for epic poems… the combined product of nature and nurture which have been shaped by the judgment (aesthetic and political) of countless constant gardeners” (628).

Of course, these assertions seem strange if we don’t look at other Homeric trees. For me, a signal moment in epic poetry comes when Odysseus is authorized to build a raft to escape from Ogygia and try to return home. The narrative pays special attention to enumerating the trees and specifying Odysseus’ skill in using them:

Odyssey 5.238-262

“She gave him the smooth axe and then took him on the path

To the farthest part of the island where the tale trees were growing,

Alder, ash and fir trees reaching to the sky,

Dry for a long time, long-seasoned, perfect for sailing.

Once she showed him where the great trees were growing,

Kalypso, the beautiful goddess, returned to her home,

While he was cutting out planks. The work went quickly.

He picked out twenty altogether and cut them with bronze.

He skillfully planed them down and made them straight with a level.

At the same time, the shining goddess Kalypso was bringing him augers

And he drilled all the pieces and fit them together.

As wide as a man who is skilled in wood-working

Traces out the line of a merchant ship—that’s

How wide Odysseus made his skiff.

Once he set up the deck beams he attached them to the

Close-placed ribs. And then he finished out the raft with long gunwales.

He fashioned a mast and placed on it a yard-arm.

He also made a rudder to steer with and then

He fashioned willow-branches and brush into a wall

To stand against the waves around the vessel.

And then Kalypso brought him a bolt of cloth

To make into a sail. He crafted that too, skillfully.

He tied into the raft braces, and restraints, and sheets

And using levers moved it down toward the shining sea.

It was the fourth day and everything was complete.”

…· ἦρχε δ’ ὁδοῖο

νήσου ἐπ’ ἐσχατιήν, ὅθι δένδρεα μακρὰ πεφύκει,

κλήθρη τ’ αἴγειρός τ’, ἐλάτη τ’ ἦν οὐρανομήκης,

αὖα πάλαι, περίκηλα, τά οἱ πλώοιεν ἐλαφρῶς.

αὐτὰρ ἐπεὶ δὴ δεῖξ’ ὅθι δένδρεα μακρὰ πεφύκει,

ἡ μὲν ἔβη πρὸς δῶμα Καλυψώ, δῖα θεάων,

αὐτὰρ ὁ τάμνετο δοῦρα· θοῶς δέ οἱ ἤνυτο ἔργον.

εἴκοσι δ’ ἔκβαλε πάντα, πελέκκησεν δ’ ἄρα χαλκῷ,

ξέσσε δ’ ἐπισταμένως καὶ ἐπὶ στάθμην ἴθυνε.

τόφρα δ’ ἔνεικε τέρετρα Καλυψώ, δῖα θεάων·

τέτρηνεν δ’ ἄρα πάντα καὶ ἥρμοσεν ἀλλήλοισι,

γόμφοισιν δ’ ἄρα τήν γε καὶ ἁρμονίῃσιν ἄρασσεν.

ὅσσον τίς τ’ ἔδαφος νηὸς τορνώσεται ἀνὴρ

φορτίδος εὐρείης, εὖ εἰδὼς τεκτοσυνάων,

τόσσον ἐπ’ εὐρεῖαν σχεδίην ποιήσατ’ ᾿Οδυσσεύς.

ἴκρια δὲ στήσας, ἀραρὼν θαμέσι σταμίνεσσι,

ποίει· ἀτὰρ μακρῇσιν ἐπηγκενίδεσσι τελεύτα.

ἐν δ’ ἱστὸν ποίει καὶ ἐπίκριον ἄρμενον αὐτῷ·

πρὸς δ’ ἄρα πηδάλιον ποιήσατο, ὄφρ’ ἰθύνοι.

φράξε δέ μιν ῥίπεσσι διαμπερὲς οἰσυΐνῃσι,

κύματος εἶλαρ ἔμεν· πολλὴν δ’ ἐπεχεύατο ὕλην.

τόφρα δὲ φάρε’ ἔνεικε Καλυψώ, δῖα θεάων,

ἱστία ποιήσασθαι· ὁ δ’ εὖ τεχνήσατο καὶ τά.

ἐν δ’ ὑπέρας τε κάλους τε πόδας τ’ ἐνέδησεν ἐν αὐτῇ,

μοχλοῖσιν δ’ ἄρα τήν γε κατείρυσεν εἰς ἅλα δῖαν.

τέτρατον ἦμαρ ἔην, καὶ τῷ τετέλεστο ἅπαντα·

Here we find a balance between nature and skill, between the material found and offered and the creative power of a maker authorized by a god. If the trees at the end of the Odyssey are symbols of tales that might be told, these Ogygian planks are echoes of stories that were told and lost. They also tell us about the relationship between narrative agent and story. As I write in my recent Many-Minded Man: “In this passage’s detail and the dramatization of Odysseus’s labors, the epic offers an anticipatory metaphor for the rebuilding of the hero’s identity. The material available has been there for years—it is not of Odysseus’s own making, but his skill and agency are critical for forming it into something new, something that can make a path or journey of its own. The selection of the trees stands in for the selection of stories and aspects of the self that will be reassembled as Odysseus journeys home.” ( 2020, 11).

But in this analysis, I might focus overmuch on the epic’s hero and not enough on the epic stuff itself. There is a relationship between the basic matter (the wood, the trees) and the stuff matter makes: ships, homes, vessels of meaning and vessels for meaning. It may be too cute to juxtapose, but there may be more to the Greek word for “matter” hule, which can also mean wood, than meets the eye.

Epic is deeply concerned with what comes after and some of its figures, like Hektor, imagine singular monuments, tombs that can be seen and act as reminders for men to come. In a way, the grave is a kind of scar left on the earth conveying its own story. But groves of trees and the ships they provide can carry on meaning and life in different ways. I am reminded here of a brief aside from the Iliad.

Iliad 5.59-68

“Mêrionês then killed Phereklos, the son of the carpenter,

Son of Joiner, who knew who to fashion all sorts of intricate tings

With his hands. Pallas Athena loved him especially.

He is the one who designed Alexander’s fantastic ships,

Those kindlers of evil which brought evil on all the Trojans

And on him especially, since he understood nothing of the divine prophecies.

Well, Mêrionês, once he overtook him in pursuit,

Struck him through the right buttock. The sharp point

Went straight through his bladder under the bone.

He fell to his knee and groaned. Then death overtook him.

Μηριόνης δὲ Φέρεκλον ἐνήρατο, τέκτονος υἱὸν

῾Αρμονίδεω, ὃς χερσὶν ἐπίστατο δαίδαλα πάντα

τεύχειν· ἔξοχα γάρ μιν ἐφίλατο Παλλὰς ᾿Αθήνη·

ὃς καὶ ᾿Αλεξάνδρῳ τεκτήνατο νῆας ἐΐσας

ἀρχεκάκους, αἳ πᾶσι κακὸν Τρώεσσι γένοντο

οἷ τ’ αὐτῷ, ἐπεὶ οὔ τι θεῶν ἐκ θέσφατα ᾔδη.

τὸν μὲν Μηριόνης ὅτε δὴ κατέμαρπτε διώκων

βεβλήκει γλουτὸν κατὰ δεξιόν· ἣ δὲ διαπρὸ

ἀντικρὺ κατὰ κύστιν ὑπ’ ὀστέον ἤλυθ’ ἀκωκή·

γνὺξ δ’ ἔριπ’ οἰμώξας, θάνατος δέ μιν ἀμφεκάλυψε.

Ok, this passage may seem unconnected and offering it may seem indulgent even for me, but consider the way Phereklos is marked out as a carpenter’s son and how the ships that carried Paris to war are positioned as the vehicles of evil for them all. While as scholiast (Schol. bT ad Il.5.59) glosses the name Phereklos as “one who brings the turmoil of war through the ships” (Φέρεκλος ὁ φέρων κλόνον διὰ τῶν νέων), I would also like to believe that name Phere-klos, might make someone think of ‘fame-bringer’. And the connection between poetic fame and the activity of the war arises elsewhere in this passage two.

Note that the this Phere-klos is the son of Harmonidês, a man who, according to the passage, is the one who build the ships “the bringers of evil” (ἀρχεκάκους) for Paris (those ships which carried him from Troy to Sparta…). The name Harmonidês is not insignificant: Gregory Nagy has etymologized Homer as “one who fits the song together”. Phereklos’ father is a “craftsman” (“tektôn”) who built the very ships that allowed his son (and Paris) to bring the conflict to Troy and generate the fame of the songs it generated. Here, the ships are positioned as the first steps in evil, but I would suggest, that as the means by which the songs themselves travel across the sea, the ships are, as products of specialized craftsmen, both metonymns for the stories themselves and necessary vehicles for their transmission.

And here, even if asymmetrical, I find myself considering a life-cycle of Homeric trees: the way one set were cut down to fan the flames of war that launched myriad ships; that others fell to bring Odysseus home to gaze upon his ancestral orchards, potentials tales to be told or curtailed…once Odysseus journeys to a land where no one remembers the sea.