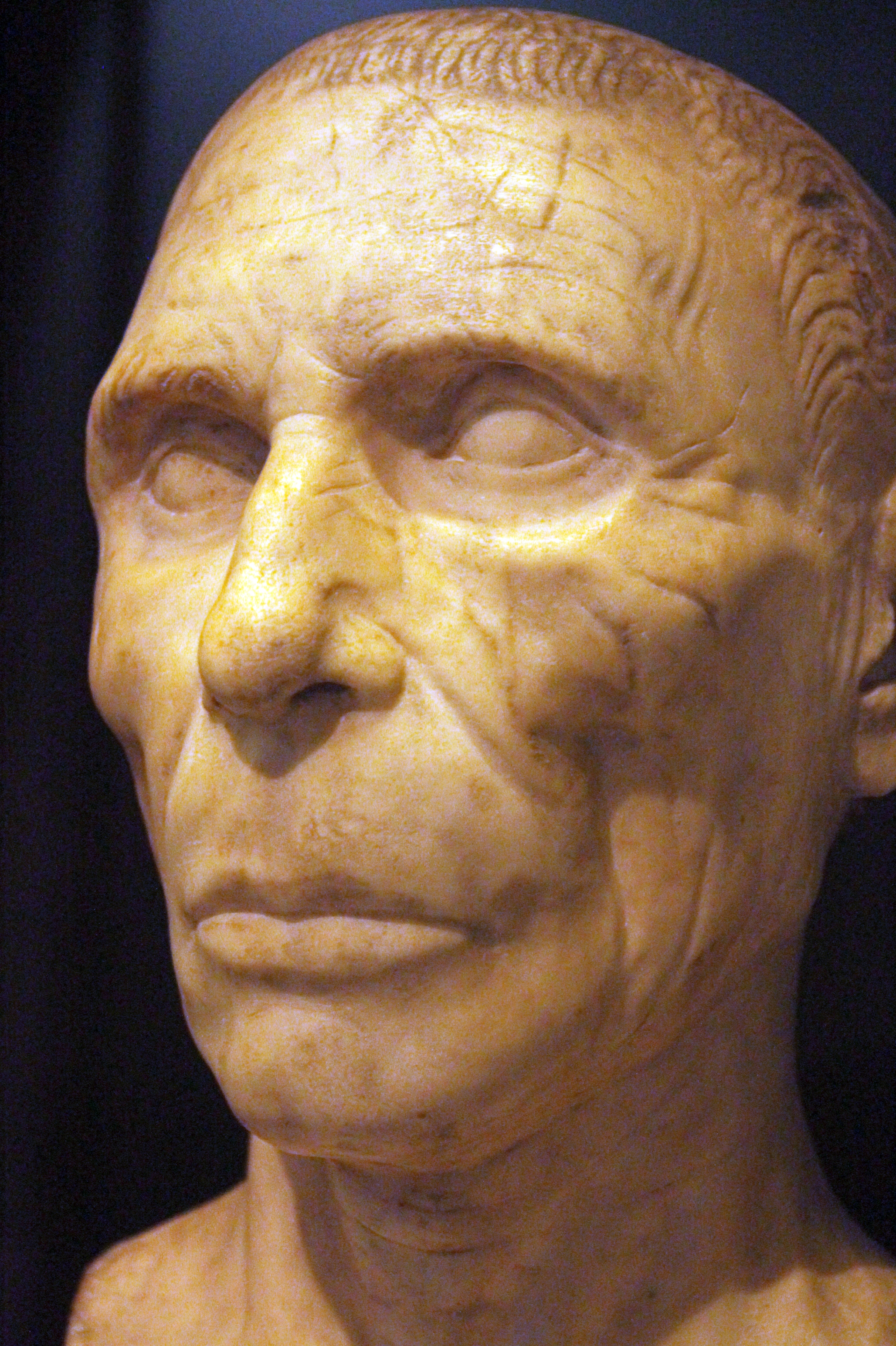

Previously we have posted about Cicero’s comments about the Ides of March to Brutus. Here is a letter from Brutus complaining about Cicero.

Letters: Brutus to Atticus, I.17

“You write to me that Cicero is amazed that I say nothing about his deeds. Since you are hassling me, I will write you what I think thanks to your coaxing.

I know that Cicero has done everything with the best intention. What could be more proved to me than his love for the republic? But certain things seem to me, what can I say, that the most prudent man has acted as if inexperienced or ambitiously, this man who was not reluctant to take on Antony as an enemy when he was strongest?

I don’t know what to write to you except a single thing: the boy’s desire and weakness have been increased rather than repressed by Cicero and that he grinds on so far in his indulgence that he does not refrain from invectives that rebound in two ways. For he too has killed many and he must admit that he is an assassin before what he objects to Casca—in which case he acts the part of Bestia to Casca—

Or because we are not tossing about every hour the Ides of March the way he always has the Nones of December in his mouth, will Cicero find fault in the most noble deed from a better vantage point than Bestia and Clodius were accustomed to insult his consulship?

Our toga-clad friend Cicero brags that he has stood up to Antony’s war. How does it profit me if the cost of Antony defeated is the resumption of Antony’s place? Or if our avenger of this evil has turned out to be the author of another—an evil which has a foundation and deeper roots, even if we concede <whether it is true or not> those things which he does come from the fact that he either fears tyranny or Antony as a tyrant?

But I don’t have gratitude for anyone who does not protest the situation itself provided only that he serves one who is not raging at him. Triumphs, stipends, encouragement with every kind of degree so that it does not shame him to desire the fortune of the man whose name he has taken—is that a mark of a Consular man, of a Cicero?

1Scribis mihi mirari Ciceronem quod nihil significem umquam de suis actis; quoniam me flagitas, coactu tuo scribam quae sentio.

Omnia fecisse Ciceronem optimo animo scio. quid enim mihi exploratius esse potest quam illius animus in rem publicam? sed quaedam mihi videtur—quid dicam? imperite vir omnium prudentissimus an ambitiose fecisse, qui valentissimum Antonium suscipere pro re publica non dubitarit inimicum? nescio quid scribam tibi nisi unum: pueri et cupiditatem et licentiam potius esse irritatam quam repressam a Cicerone, tantumque eum tribuere huic indulgentiae ut se maledictis non abstineat iis quidem quae in ipsum dupliciter recidunt, quod et pluris occidit uno seque prius oportet fateatur sicarium quam obiciat Cascae quod obicit et imitetur in Casca Bestiam. an quia non omnibus horis iactamus Idus Martias similiter atque ille Nonas Decembris suas in ore habet, eo meliore condicione Cicero pulcherrimum factum vituperabit quam Bestia et Clodius reprehendere illius consulatum soliti sunt?

Sustinuisse mihi gloriatur bellum Antoni togatus Cicero noster. quid hoc mihi prodest, si merces Antoni oppressi poscitur in Antoni locum successio et si vindex illius mali auctor exstitit alterius fundamentum et radices habituri altiores, si patiamur, ut iam <dubium sit utrum>ista quae facit dominationem an dominum [an] Antonium timentis sint? ego autem gratiam non habeo si quis, dum ne irato serviat, rem ipsam non deprecatur. immo triumphus et stipendium et omnibus decretis hortatio ne eius pudeat concupiscere fortunam cuius nomen susceperit, consularis aut Ciceronis est?