This post is a slightly edited version of a thread I posted on twitter yesterday #WorldsNotAuthors

Strabo, 1.2.7

“Humans love to learn; loving stories is a prelude to this. This is why children start by listening and making a common ground in stories.”

φιλειδήμων γὰρ ἅνθρωπος, προοίμιον δὲ τούτου τὸ φιλόμυθον. ἐντεῦθεν οὖν ἄρχεται τὰ παιδία ἀκροᾶσθαι καὶ κοινωνεῖν λόγων ἐπὶ πλεῖον.

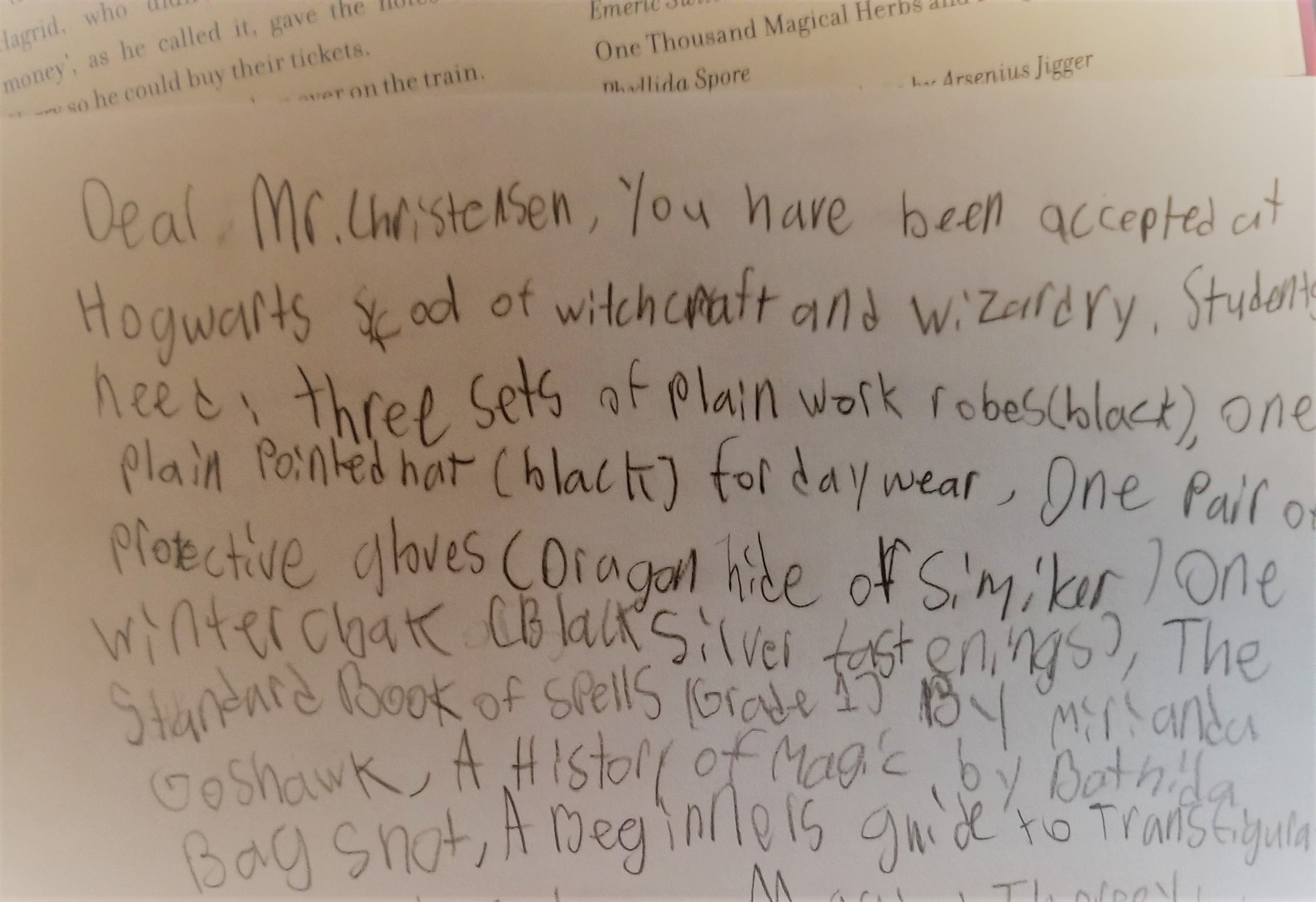

This week, I discovered that my children were secretly making holiday gifts for each other. I walked into the office and found my daughter writing a Hogwarts acceptance letter for her brother, because he wants magic to be real.

Let’s just say that after witnessing this I left the room and had a sudden, prolonged attack of itchy eyes.

I was crying in part because the moment was just so sweet and emerged from a year of the children learning to love the world of Harry Potter. But this was the same day J. K. Rowling was in the news for supporting bigotry, for showing public support of a transphobic UK Academic. (And a lot of analysis online has made it clear that this is not a casual mistake, that she has a pattern of antagonism towards transgender people.) There was a lot of justifiable anger and disappointment online, as several communities wrangled with how to wrangle with this.

This is not, of course, the first time the author of the Harry Potter series has courted controversy. At times she has expressed offensive or poorly nuanced political views; at others, she has seemed to hastily adapt her fictional world to the realities of the contemporary one, claiming, for example, that Dumbledore was always gay.

Euripides, Suppliant Women, 913-917

“For even an infant learns to speak

And listen to things he has no understanding of.

Whatever someone learns, he wants to save

For old age. So, teach your children well.”

..εἴπερ καὶ βρέφος διδάσκεται

λέγειν ἀκούειν θ᾿ ὧν μάθησιν οὐκ ἔχει.

ἃ δ᾿ ἂν μάθῃ τις, ταῦτα σῴζεσθαι φιλεῖ

ἐς γῆρας. οὕτω παῖδας εὖ παιδεύετε.

As many of my former and current students know, I resisted the whole Harry Potter phenomenon for years because I was already teaching when it started (and was thus too cool for the narrative), because, like others, I was weaned on other narratives which had seemed forgotten, like Lloyd Alexander’s cycle, Susan Cooper’s Dark is Rising Sequence, or the unending Wheel of Time. But I was mostly frustrated that at its core, the Harry Potter books are just the same old heroic narrative recycled

As I have written about before the heroic pattern has a great potential to cause harm. The basic heroic narrative is regressive, heteronormative, male-centered, and often, when realized in a western context, racist. It limits roles, sets people up for severe disappointment, and can also eventuate in violence

I was worried about some of these influences when my kids started reading the books because narratives can have such powerful impact on how we view ourselves in the world. My children are young, already shaped by social expectations for gender. The Potter books don’t really give much space to women, they cast good and evil in a rather stark divide (until near the end), and they tokenize non-white characters. My children are bi-racial and are not Christian.

I was worried they would not see themselves in the books or would simply see themselves as peripheral. When it comes to people who look like them or have names closer to theirs, things get a little bleak: The Indian characters in the book are mere UK colonial props, like chicken curry in a pub.

But oh, whatever my reservations, how they fell in love! My daughter, who had read eagerly for a bit but then got overwhelmed by longer books, started listening to the audiobooks while we were driving and then would immediately go to the book when we got home. Before long, she would listen while reading and made a huge leap in her confidence and comprehension. My son, precocious in the way only younger brothers can be, tore through the books in a few months. And then started again a second time.

Seneca, EM 3.3

“What you see happen to children happens to us, too, who are but slightly greater children.”

quod vides accidere pueris, hoc nobis quoque maiusculis pueris evenit.

Experiencing the books together was something something I will cherish until I die. We all listened together in the car and I cried uncontrollably at their smiles when Gryffindor won the house cup at the end of the first book. I heard the stories through their eyes and listened as they debated who was good and bad, cringed at the burgeoning Romances, and wept when their favorite characters died.

Over six months we listened to all the books together, they read them separately, and they watched the movies. Relatives gave them Harry Potter Legos. A babysitter introduced them to the online House quiz. My daughter has a Ravenclaw Scarf; her brother, like Harry himself, is sometimes Slytherin, sometimes Gryffindor. They are now re-listening to the books any time we drive.

In many ways this is different from the way I experienced narratives with my parents: my father was deaf and we would sometimes talk about what we read, but we rarely ever watched movies together (until closed caption was common) and my mother’s genre interests rarely overlapped with mine. My siblings were almost always a little young for what I was reading. Such a deep, shared experience was new to me.

But as a parent, it was also not free of certain burdens. As someone who studies narrative and myth, moreover, I have been really cautious about the stories we tell them from the beginning. Because I was swept away with them to Wizarding world, I don’t know what they have absorbed and what they haven’t, so the world is theirs now. But when the creator of this series makes pronouncements in public, I hear it, but they do not. They don’t know who JK Rowling is. They know the story and they love it. They remake the stories in their play and they find their own lives within it.

I know from the comments in response to the twitter thread that there is a little too much naivete at work here, that the extent of the damage a story can do is unacknowledged, and that the fame and money our love of narrative bestows on authors gives them outsize power in the world. A boycott makes sense, from this perspective.

Yet, there is some wisdom in the child’s eye view here. As adults, we lionize authors/creators/artists mistakenly, partly because of the author/god metaphor but also because of capitalism and individualism. But this is a backwards way of seeing human creativity and creation. We need to change the way we see what artists do in the world; we need to change the way we talk about it.

As a Homerist I fight the tendency to worship authors and essentialize the relationship between them and their work all the time. I am always asserting that (1) there was no Homer and, at best, the name is a metonym and (2) more importantly, even if there were a Homer or if we could isolate a single singer who put together the Iliad and the Odyssey, Epic and literature are a product of interaction between audiences and performers over time. Everyone always wants to talk about the performer but not the audience. Everyone wants to talk about the author, but it is the reader who matters more.

Languages, story-worlds, plot conventions, and all the other things that make narratives possible are products of groups and multiple creators: even individual poets do what they do by contrasting with what is already there. We have a modern collective insanity when it comes to valuing the contribution of individuals and rewarding them. Let me be clear: I don’t think it is a problem if someone creates something people love and gets rich. I just think it is a problem that they see getting rich as valorizing whatever they do and say apart from the work of art.

Sometimes bad people make good things; other times good people make bad things. But people always change and the work changes too. We face particular problems in our society when someone like Orson Scott Card gets rich from creative work and then uses it to hurt people. Let’s be clear here: the problem is not narrative or even Orson Scott Card, the problem is the cancerous effect that money has on human relationships and identity.

I have two responses to this, one a coward’s and one impractical. First, I don’t believe you can buy your way to or from virtue. Capitalism is so deeply thievery and exploitation that to refuse to spend on one corruption is merely to spend on another one. The choice is illusory agency. Of course, it is probably prevarication to say that how we spend does not matter. So, second, for the bold, infringe on copyright; for the more law-abiding, public libraries weaken the advantages that our passions confer.

Our passions are so often unpredictable. Works that move people, that change their lives, don’t necessarily have to be great pieces of art. As others have said, the Potter books are not terribly well-written and much of it is silly, retrograde, or derivative. But it works as story because young people are so willing to fall deeply, and madly in love with a world with rules, magic, and endings.

This inspiration comes from countless other readers, writers, storytellers, and singers. I think that ‘great’ authors just end up being in the right place and right time and have the privilege and luck to tell their stories and have them heard. They also need the cultural prestige and position to do so.

Because I have read the Homeric epics without author for so long and have spent so many years thinking about orality, authorship, and reader reception, it is easy for me to dismiss all authors. I extend this to musicians all the time and have often found myself arguing with my brother about whether or not it matters what a songwriter says a song is about. When artists release their work into the world it becomes something else. But it was already something different before it left them because our languages, images, and narrative patterns are in every part compressed potentials of meaning we don’t fully comprehend at any given moment.

My favorite metaphor to help me understand this comes from Plato’s dialogue, the Ion. Plato has Socrates provide a simile to the rhapsode Ion in about a magnet: he argues that a singer is like a metal ring which is endowed with magnetic power because from another magnetic ring (poet) touching a magnet (the muse/god). He makes it very clear that the audience is part of this process.

535e-536a

“Do you understand that the audience is the last of the rings which I was describing as transmitting through one another the power from the Herakleian stone and that you are the middle as the rhapsode and interpreter—that the poet himself is the first ring? The god moves the soul of all of these people wherever he wants, stringing the power from one into another.”

οἶσθα οὖν ὅτι οὗτός ἐστιν ὁ θεατὴς τῶν δακτυλίων ὁ ἔσχατος, ὧν ἐγὼ ἔλεγον ὑπὸ τῆς Ἡρακλειώτιδος λίθου ἀπ᾽ ἀλλήλων τὴν δύναμιν λαμβάνειν; ὁ δὲ μέσος σὺ ὁ ῥαψῳδὸς καὶ ὑποκριτής, ὁ δὲ πρῶτος αὐτὸς ὁ ποιητής ὁ δὲ θεὸς διὰ πάντων τούτων ἕλκει τὴν ψυχὴν ὅποι ἂν βούληται τῶν ἀνθρώπων, ἀνακρεμαννὺς ἐξ ἀλλήλων τὴν δύναμιν.

This is my favorite way of thinking about artistic creation: imagine if the first ring is not god, but instead human culture in its messiness, in its synchronic and diachronic forms. Authors convey this power and direct it, and audiences transmit it on. I would even argue that magnetism is a good starting metaphor, but it fails to explain the multidirectional network of creative acts, how some nodes can weaken or strengthen their force, how feedback loops from recipient back to speaker can change the force, and how none of us can fully understand the scope of narrative creation because we are inside of not outside of time.

Seneca, De Tranquillitate Animi 8

“Quoting the good words of a bad author will never shame me.”

Numquam me in voce bona mali pudebit auctoris

So, when it comes to the importance of authors, I usually take a pretty hard stance. If JKR wasn’t going to write Harry Potter someone like her would have eventually. Our world was ready for it and the audience was willing to make it real.

When authors turn out to disappoint us—and they always will because they are human and not heroes in their own stories—we can ignore them and detach them from their narratives with no guilt. Perhaps we need to defund them or deplatform them at times, but the story lives beyond the storyteller before the tale is ever told. There’s a larger question here we need to have about loving or praising ‘good’ art from ‘bad’ people.

This doesn’t mean that their stories themselves are innocent. The HP universe has deep body image problems, is certainly ableist, racist and heteronormative. But it is not any of these things because of the author in particular: these stories reflect our world. They reflect us. More progressive authors like Ursula Le Guin or even Robert Heinlein pushed us to rethink our assumptions about gender and sex; and more recently N. K. Jemesin, Ann Leckie, or Ada Palmer help us to see how we are by depicting how we aren’t. And as we grow older and wiser as audiences, we can see these things and make new, better stories.

And I hope to read many of these stories with my children. Unfortunately, many of them also depict sexual acts and I am not ready for that just yet. For now, I am going to just wait to see the look on my son’s face when he gets his acceptance letter. It will destroy me. But, that’s probably because I’m a Hufflepuff, which is something my children, not JKR, taught me.

Strabo 1.8

“Whenever you also consider the amazing and the disturbing, you amplify the pleasure which is a magic charm for learning. In the early years, we must use this sort of thing to entice children, but as their age increases we must lead them to a knowledge of reality as soon as their perception has gotten stronger and they no longer need much cajoling. Every illiterate and ignorant person is in some way a child and loves stories like a child.”

ὅταν δὲ προσῇ καὶ τὸ θαυμαστὸν καὶ τὸ τερατῶδες, ἐπιτείνει τὴν ἡδονήν, ἥπερ ἐστὶ τοῦ μανθάνειν φίλτρον. κατ᾿ ἀρχὰς μὲν οὖν ἀνάγκη τοιούτοις δελέασι χρῆσθαι, προϊούσης δὲ τῆς ἡλικίας ἐπὶ τὴν τῶν ὄντων μάθησιν ἄγειν, ἤδη τῆς διανοίας ἐρρωμένης καὶ μηκέτι δεομένης κολάκων. καὶ ἰδιώτης δὲ πᾶς καὶ ἀπαίδευτος τρόπον τινὰ παῖς ἐστι φιλομυθεῖ τε ὡσαύτως·

. . . Thank-You: Amazing PoV !!! … and gentle… and sincere.

Happy Holidays!

.

(Some links for your kids: maybe they will find something useful:)

> CRAFTS > https://www.thesprucecrafts.com/kids-crafts-4162869

https://www.thesprucecrafts.com/

Brilliant.

Reblogged this on Word-for-Sense and Other Stories and commented:

Joel Christensen is one of my favorite people on this planet, and I am incredibly lucky and privileged to know him and learn from him. His words here about Harry Potter and the relationship between author, text, and reader resonate deeply within me, and I appreciate the personal perspective he lends to the discussion of the topic at hand. As far as my personal opinion regarding JK Rowling is concerned, the books and the fandom around them and all of the great things that fans have created can stand on their own, and don’t need to be defined by JKR and her opinions. She may have created the original text, but most of its meaning exists in what the world has done with it since then.

Thanks Talia. You’re one of my favorites too!